Epidemiology: Monkey pox was first described in 1958 in captive Asiatic monkeys, but it is only found naturally in Africa, primarily in remote villages in Central and West Africa, near tropical rainforests. The first human case was recognized in Zaire in 1970. Since then, more than 200 cases have been reported, mainly in Zaire (now Democratic Republic of Congo), but also in Liberia, Nigeria, Ivory Coast, Cameroon, Sierra Leone and most recently, in Sudan. In 2003, human cases were diagnosed in the USA, as a result of global commerce of exotic pets, with rodents playing a role as potential reservoirs, although this is the only time monkey pox has occurred outside of Africa.

It is not known whether the primary maintenance hosts are chimpanzees, other primates or small mammals. Most patients give a clear account of contact with monkeys which they have caught and/or eaten. Most cases occur during the dry season and children are affected more than adults.

Pathology and Pathogenesis.

The monkey pox virus is morphologically indistinguishable from variola. In culture, the pocks on chick chorioallantoic membrane are slightly larger and more haemorrhagic than those caused by variola. Unlike variola, monkey pox virus is pathogenic in rabbits, and has a higher temperature ceiling for growth. It grows readily in green monkey and rodent cell cultures.

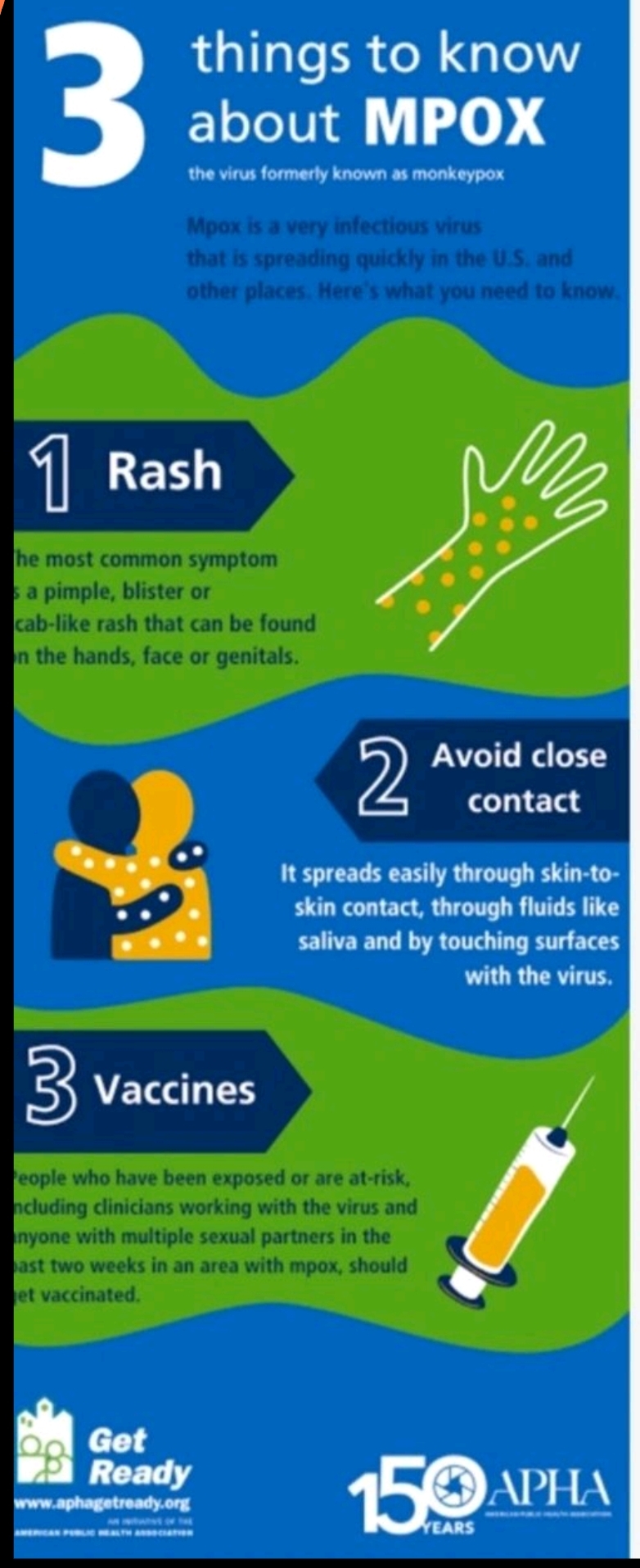

Humans are infected by direct contact with blood, body fluids, or skin lesions of infected animals or by droplet spread via the respiratory tract. The disease is not readily transmitted from person to person, but secondary cases have been recorded as a consequence of contact with respiratory secretions, skin lesions or infected fomites. The attack rate is 10% in susceptible individuals in close contact with a primary case, in contrast to smallpox infection in which it was 20%. Little tertiary spread occurs, and epidemics are not a feature.

The pathogenesis is similar to that of smallpox, with an incubation period of about 12 days (range 5–17 days), viraemia and dissemination to organs and skin. The smallpox-like rash evolves over 2–4 days, followed by complete recovery after 2–3 weeks. Only rarely does human monkey pox result in death (<10% of cases). There is well-defined immunity to reinfection, and complete cross immunity with variola and vaccinia. Monkey pox has never been reported to occur in an individual vaccinated for smallpox.

Clinical Features.

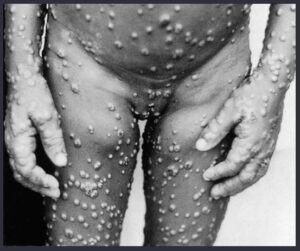

The clinical manifestations of monkey pox can be divided into two stages. The onset is abrupt with a prodromal illness lasting 2–5 days characterized by fever, severe headache, myalgias, back pain, prostration and characteristically, marked lymphadenopathy, particularly cervical, submandibular and sublingual. On the 3rd to 5th days, the exanthem appears; this consists of a single crop of discrete papules, more abundant on the face and extremities than on the trunk. The soles of the feet and palms are usually involved. The papules form pustules which become umbilicated and are covered with crusts which separate after about 10 days, leaving small scars. The number of lesions varies from a few to several thousand, affecting the oral mucosa (in 70% of cases), genitalia (30%), conjunctivae (20%) and the cornea. Resolution of the illness takes 2–3 weeks. Mild atypical cases occur in which there may be fewer than 10 lesions, separation of the crusts occurring by the 5th day. Complications include keratitis, encephalopathy, secondary bacterial skin infection, gastrointestinal disease, and airway obstruction due to severe lymphadenopathy. The differential diagnoses include smallpox, chickenpox, measles, bacterial skin infections, scabies, syphilis and drug reactions.

Monkey pox, with characteristic inguinal and femoral lymphadenopathy.

Diagnosis.

The diagnosis is based on clinical findings, epidemiology and a history of contact with monkeys. Lymphadenopathy is an important distinguishing feature from smallpox. A definitive diagnosis can be achieved by identification of the virus by PCR, electron microscopy, isolation in cell culture, antigen detection tests and antibody detection by ELISA.

Management.

Treatment is symptomatic and supportive.

Prevention.

Previous smallpox vaccination is protective in most persons. During outbreaks, contact precautions are important to prevent spread. Animal-to-human exposure can be prevented through awareness of the illness and source of infection, appropriate handling of sick animals and animal products, and complete cooking of products for human consumption.